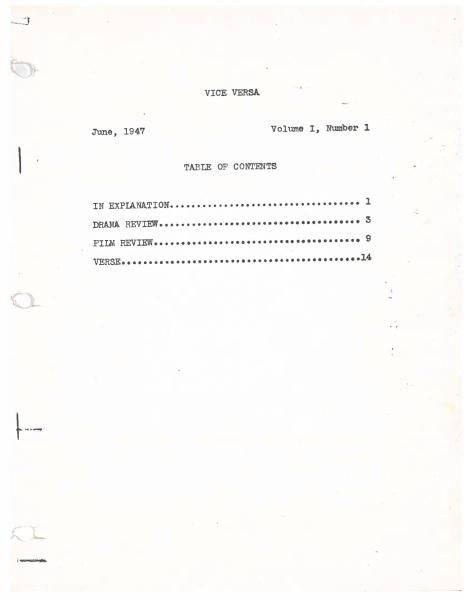

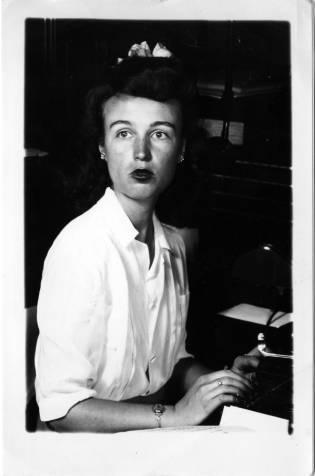

The first issue of Vice Versa was published in June 1947. At just fourteen pages in length, the lesbian magazine was the first of its kind in the United States. It was published by Lisa Ben, a young lesbian and recent arrival to Los Angeles from Northern California. Ben was able to create the magazine thanks to her job as a secretary at RKO Studios, where her boss instructed her to “look busy” even when she had no work to do (Faderman 106). Ben capitalized on that opportunity to found Vice Versa, which she typed by hand, edited, and wrote nearly all of the content for across the magazine’s nine-issue run.

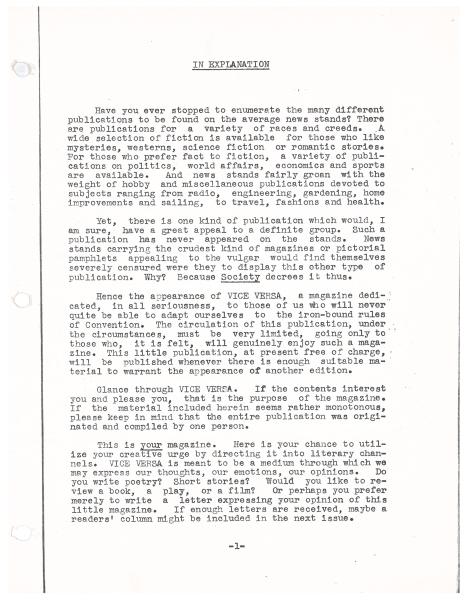

Lisa Ben was born Edythe Eyde in Northern California in 1921. She chose her pen name, Lisa Ben, as an anagram of “lesbian.” From June 1947 to February 1948, Ben produced nine issues of Vice Versa, with just ten copies of each issue. The magazine was released monthly and . In issue one, Eyde articulated her goals for Vice Versa, describing it as, “a magazine dedicated, in all seriousness, to those of us who will never quite be able to adapt ourselves to the iron-bound rules of Convention” (Issue 1, 1). She was aware of the magazine’s singularity as a lesbian publication and offered a bold vision for her work, even as she acknowledged its precarious position in a society hostile to lesbians.

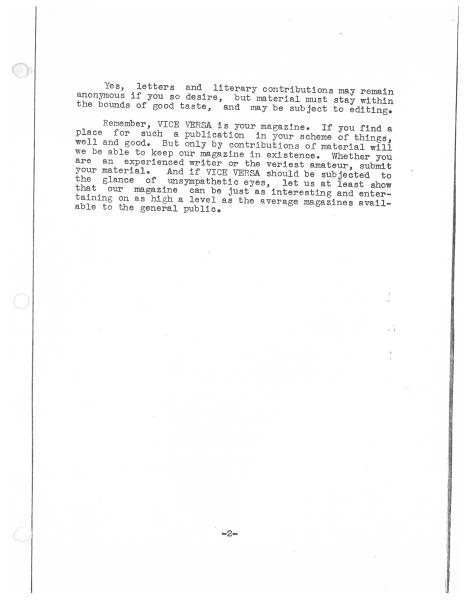

There was a very real threat of arrest for anyone caught distributing queer materials, including magazines like Vice Versa. Anonymity and pen names like “Lisa Ben” were one common way of allaying these fears within early queer publishing. The role of anonymity was something Ben was negotiating in the first few issues of Vice Versa. In Issue 2, Ben’s response to a reader’s letter stated that the magazine will keep their contributors anonymous if they desire that, but that it is not the policy to require anonymity. Just one issue later, however, Ben changed her position in a response to a reader who indicated their desire to print their name along with their letter. Ben wrote, “in a recent conversation with friends as to the advisability of identifying literary contributors to VICE VERSA, I was counseled that it would be wiser not to do so at present” (Issue 3, 17).

In all of the issues of Vice Versa, Lisa Ben herself is never identified by name, pen or otherwise. A few other contributors are credited by name later in the run of the magazine, including R. Jamamigo and Laurajean Ermayne (the pen-name for Forrest J Ackerman, a sci fi publisher), but Ben is quick to assure readers that these are not their real names. “Authors’ true names are never used, in case this might be a deterrent factor in your sending in material,” she writes in one of her recurrent pleas to readers to submit more writing for the magazine (Issue 8, 16). The need for secrecy was a significant concern for Ben, for the protection of herself and all of the other writers who contributed to the magazine.

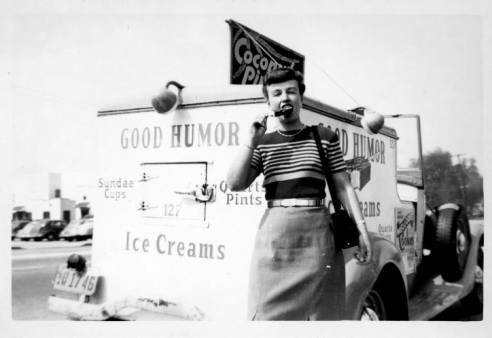

Vice Versa faced similar concerns on the distribution side. Ben stopped distributing copies through the mail early in its run, concerned about the potential dangers of being caught sending a lesbian publication in the mail. Coupled with its incredibly small print run—working alone, Ben was only able to produce ten copies of each issue—the magazine relied on in-person distribution and word of mouth to reach its readers. Ben would pass out the magazine at Los Angeles lesbian bars like the If Club (link), as well as distributing it to friends who would pass it along to other lesbians. She asked in Issue 2 that her readers keep the magazine “just between us girls,” imploring them to help protect the secrecy and therefore the longevity of the magazine. Given these methods, it is difficult to guess how many readers the magazine actually reached. Its success was entirely reliant on the emerging lesbian community at the time, as it was quietly distributed through underground personal connections.

Another difficulty that faced Vice Versa was getting content for each issue. Each magazine ranged from just eight to nineteen pages in length, nearly all of it written by Ben herself. She was successful in soliciting a few submissions from readers, including stories, book reviews, poems, and letters to the editor, but portrayed this effort as a constant struggle. The majority of the issues features pleas for more submissions and laments about the difficulty of doing all of this work herself. In Issue 1, she announced that “This is your magazine,” and implored readers to submit pieces or write her with their opinions of the magazine (Issue 1, 1). Much of the solicitation of articles had to be done in person, as Ben reflected in an anecdote at the beginning of Issue 4. A group of three lesbians arrived at Ben’s home late one night, after reading Vice Versa and being directed to Ben by a friend of hers. Ben recounted asking these women to submit pieces and one did follow through, though Ben again lamented that just one submitted instead of all three.

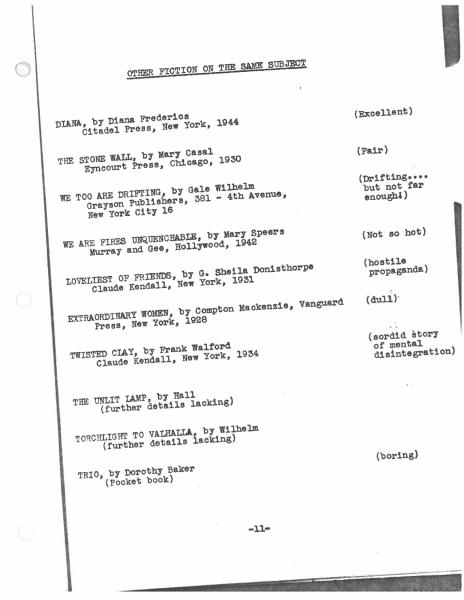

The content that did appear in Vice Versa offers a fascinating glimpse into the concerns and interests of lesbians in the late 1940s. Despite most of the writing coming from Lisa Ben, it spans a wide range of topics and styles of writing. Ben has a sharp sense of humor and a tongue-in-cheek style to much of her writing. Her review of books, theatre, and movies are one clear place where this tone comes through. In Issue 2, Ben provides a list of several books that deal with lesbian subjects, offering brief reviews of each in parentheticals beside their titles; one reads “Excellent,” another “Fair,” and another “hostile propaganda.” We Too Are Drifting gets “Drifting…but not far enough!” and she ends the list with a single word on Trio: “boring” (Issue 2, 11).

Additional interesting commentary on lesbian life of that era comes in the “Whatchama-Column,” a recurring section that featured letters to the editors and Ben’s responses. Ben and her readers discussed the variety of terms that were popular at the time for lesbians, playfully suggesting new terms or commentating on existing ones. In Issue 6, one reader asked, “Has it ever occurred to you, my sisters, that the names by which we call ourselves lack dignity?” and went on to suggest that instead of “butch,” they begin referring to the “tom-boy type” as a “clyffe,” drawing from the name of Radclyffe Hall, author of the much-celebrated lesbian book Well of Loneliness (Issue 6, 9). Ben’s response dug into the role of casual slang in lesbian community and pointed to her own use of terms like “tyke,” a replacement for the “term of questionable taste,” dyke (Issue 6, 11). The magazine reflects the variety of issues that were being negotiated within lesbian communities in this era and place.

Vice Versa ended after just nine issues. In 1948, Ben lost her job and her opportunity to produce the magazine when RKO was bought by Howard Hughes. The last issue, published in February 1948, did not reflect any awareness that it would be the final issue. She ends the issue by responding to a letter to the editor, expressing her hope that the writer would send in more work to be featured in future issues of the magazine. Despite its early and sudden end, however, Vice Versa represented a defining moment in the history of queer publications in the United States. As the first lesbian publication, it set a tone for queer publications to follow, providing an example of various methods of producing content for lesbian and gay audiences as well as methods of distribution. Ben would go on to work on other publications like the lesbian magazine The Ladder in the 1950s. Vice Versa stands as a ground-breaking moment in queer publishing, a magazine suffused with insights into the lives of lesbians in Los Angeles of the 1940s.