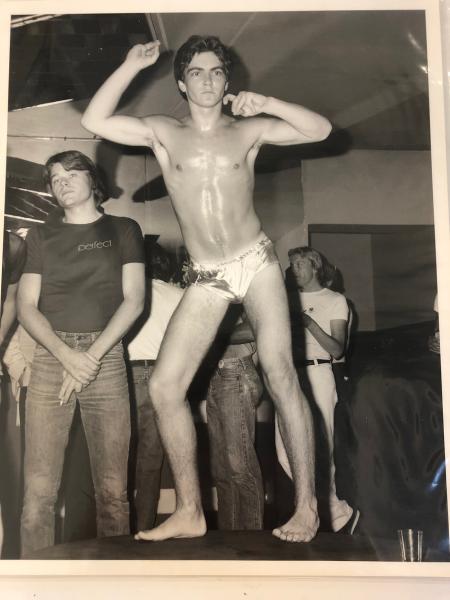

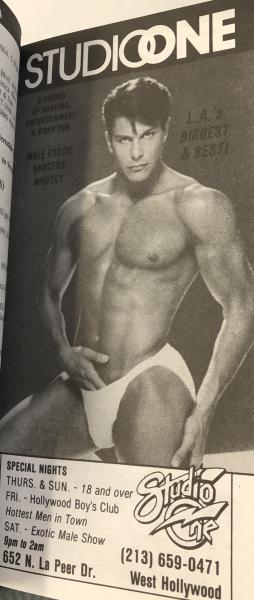

In the 1979 edition of the Bob Damron guidebook, during the height of the disco years, Studio One was characterized by its young crowd and entertainment, which included cabaret performances. It was called a “top super bar” (Damron, 1979). Its younger demographic, sometimes including teens and otherwise 20-somethings, was a core feature of the establishment. Advertisements encouraged this with Thursday and Sunday nights open to those 18 years old and up (Damron, 1979). Studio One also made a point to advertise nightly male erotic shows, their posters and guidebook ads dominated by images of young, muscular, scantily-clad men (Damron, 1979).

Another feature of the Studio was theater entertainment and dining as provided in the “Backlot.” Other advertisements boast daily shows at 10 p.m. and midnight, and dining from 7:30 p.m. until 9 p.m. One particular advertisement featured a young man with full frontal nudity and a quote from The Advocate, “excellent entertainment is always featured at the Backlot. The disco is without equal in California” (Damron, 1979). Studio One had a clear message and audience that made it one of the biggest successes in Los Angeles disco.

The secret to Studio One was its specificity and excellent execution. The owner, Scott Forbes, was dubbed “Disco King” by the Los Angeles Times in a 1976 feature. He was quoted saying “Studio One was planned, designed and conceived for gay people, gay male people” (LA Times, 1976). The same article described it as one of the most “separatist” of LA’s discos in terms of clientele, in terms of “straights or gays only” (LA Times, 1976). Forbes also fixated on the issue of “the Door,” which he thought was the demise of many discos, unwelcome patrons gaining entry. This is apparently what made Studio One what it was: a sort of gay male haven, complete with young men, erotic dancing, food, drinks, and theater.

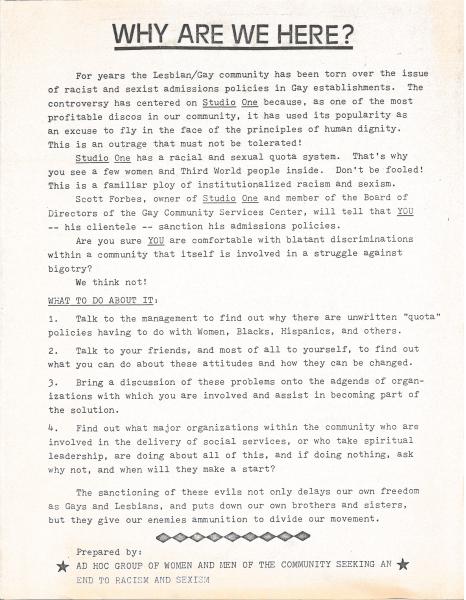

However, Studio One and Scott Forbes were criticized for their intense exclusivity. Not only were straights denied access, so too were many people of color. The LA Times asserted that “blacks as well as Chicanos say they are often denied entrance” (LA Times, 1976). Forbes saw it differently, saying that the Studio was “probably the finest run establishment in the city as far as control of people is concerned” (LA Times, 1976). Forbes admitted that ID was necessary, but other evidence from the period suggests that not one but three pieces of ID were required (Advocate). Forbes was also quoted saying that “if you look intoxicated, if you’re not dressed properly, if you smell bad, you don’t get in” (LA Times, 1976). With these policies, there was room for discrimination across class and racial lines. The LA Times itself took a side, asking “What was Scott Forbes really suggesting?” after his description of the code. It is rather well-documented that the Studio was made largely for white gay men with some money.

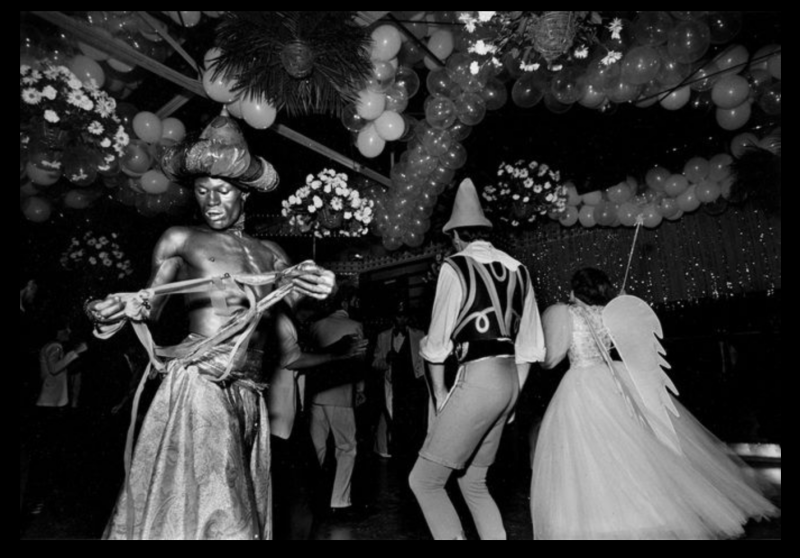

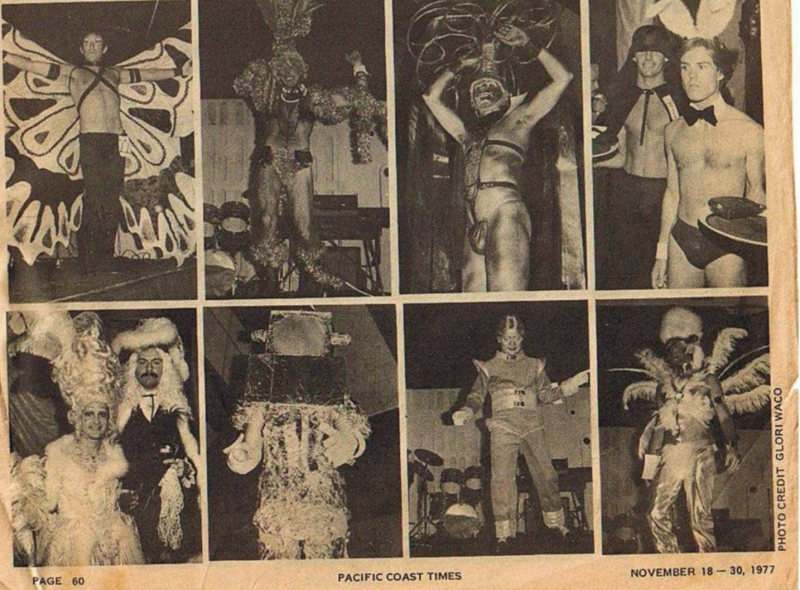

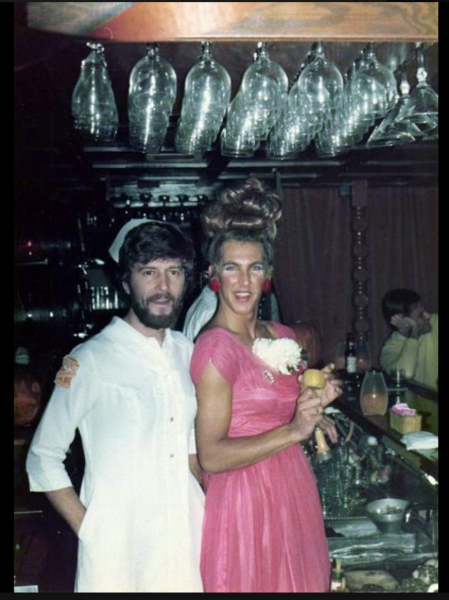

Studio One was a large and lavish space. Pictures show huge dance spaces, large bars, and hundreds of people (Facebook, Studio One). Advertisements also boasted their five rooms of dancing and entertainment (Damron, 1979). An article in the 1977 edition of the Pacific Coast Times detailed a massive Halloween celebration with pictures and descriptions of festivities. Two thousand people came, a massive circus tent was rented, there were several performers and costume contests cash prizes. Entry was $10 (Pacific Coast Times, 1977), which was significant, further illustrating its classist tendencies.

One important performer that graced the Studio One stage was gay disco legend Sylvester (Facebook, Studio One). A huge part of disco was a reclamation of traditional masculinity, generating a type of “clone” look that was prominent at Studio One. Interestingly enough, Sylvester, a black person who “performed in wildly extravagant women’s clothes” (BLK). not only gained access to Studio One but headlined. In the video of Sylvester performing at Studio One, Sylvester appears in full makeup, red hair, a women’s red sequined shawl top and jewelry. The audience dances, clearly enjoying the music (Facebook, Studio One). Sylvester had a place there, and so did many drag queens, regular performers at the Studio. Despite the racist and classist aspects of its management, Studio One remains an important and subversive space in the history of Los Angeles.

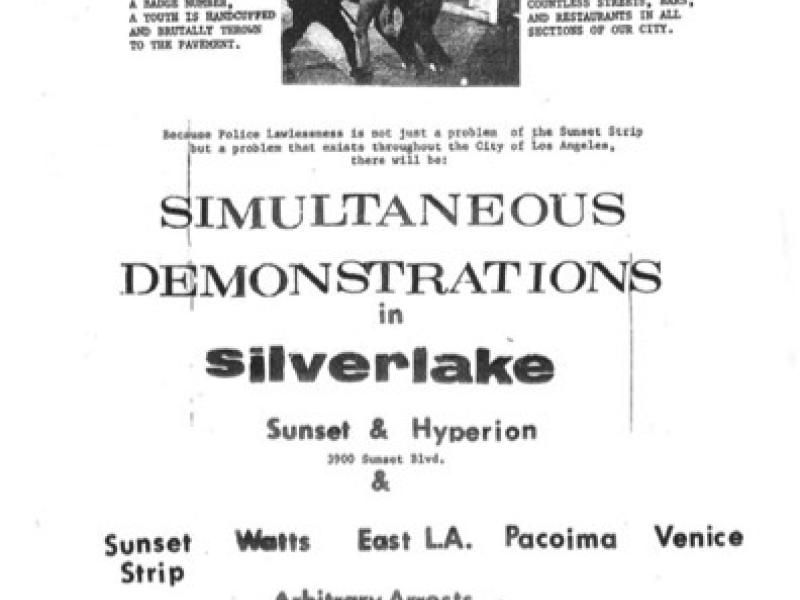

Studio One’s exclusive policies became controversial in 1975. The LGBT community fought the racist and sexist discrimination that occurred by the club and its owner to prevent those who were not apart of the white male upper class to attend. Three pieces of identification were required before even being admitted to the club and that was only if diversity quota has not been met for the night. Women and minorities were turned away from the door while white males were always admitted. The Gay Community Mobilization Committee made the most effort to shut down these practices of supremacy by sending letters of protests and community boycotts. After a series of high profile protests, Forbes agreed to their demands of removing the three-piece ID system and instead post a phone number to be used by those who feel they have been discriminated against. Later, however, Forbes backed out of his agreement and the picket lines resumed, this time not stopping until their demands were implemented. Rather than being a representation of Pride, the club became a place that stood for racist discrimination and white male privilege.