The Windup Bar acted as a second residence for many gay men around the 1950s. The concealed life for a homosexual living in the 1950s in Los Angeles directly paralleled the lack of advertising presence of gay bars in the ‘50s. Gay male figures were under the threat of police forces and could potentially lose job positions if they were discovered in the public sphere. Markedly, the 1951 Stoumen v. Reilly Supreme Court case segued to greater social opportunities for homosexuals, as it legally permitted the operation of gay bars in California. In fact, this case serves as one of the chief motivators for the owner's desire to open the Windup. In Helen Branson and Will Fellows’ book called Gay Bar, Branson expresses her sympathy for the lack of genuine opportunities for the socialization of homosexuals as she states, “lonesomeness is the phantom that hovers over every one” (83). As a result, regulars at the Windup were thrown into a nurturing environment, where they had the opportunity to mingle with those around them and form lasting relationships.

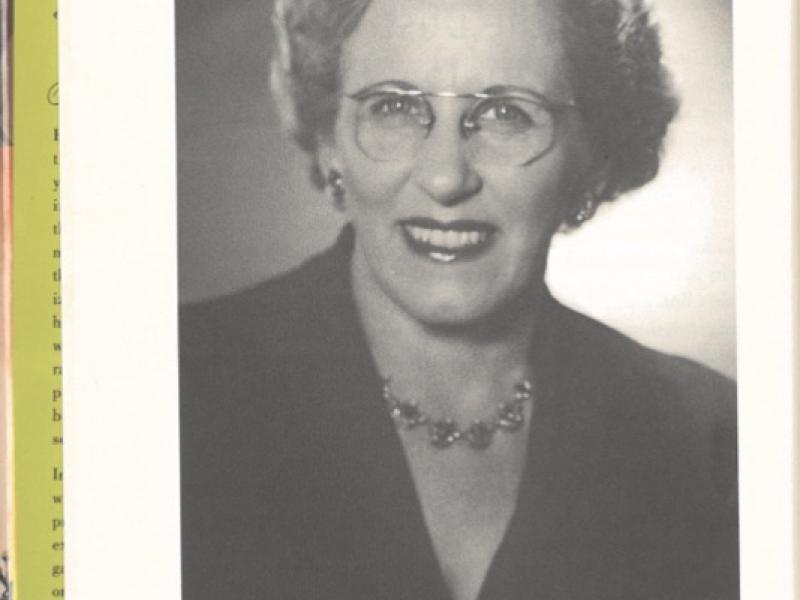

Helen Branson played a significant role in the cultivation of a unique experience for all of her bar patrons. As Branson developed friendships with countless gays in roughly the ‘40s and the ‘50s, her mission as a bar owner was more than just profit-driven: she truly believed she had a void to fill and provide opportunities for neglected gays in society. Helen’s fondness of gay men is described in Gay Bar, as she shared “My gradual integration with such groups has come through mutual affection and respect. I am at home with them” (xvii). She ensured that gay men were given a place to be themselves. She also put a great emphasis on getting to know each one of her visitors.

The Windup was managed in an ineluctable manner, as Branson oversaw the bar “with an ‘iron hand’ in a ‘not-so-velvet’ glove’” (Branson and Fellows 73). If an oblivious woman were to enter the bar, she would kindly be requested to leave by Branson in a prompt manner. Focusing on maintaining the intimate experience of her bar, Branson would interact with newcomers in a cold manner, until she got to know them on a deeper level. As a result, she would give the newcomers an unfrosted glass. Moreover, the composition of regular customers of the Windup was diverse, yet cohesive, as the patrons included business professionals, film industry professionals, designers, television actors, music composers, and actors. Given the austere risk of homosexuality in the public sphere of the 1950s, the Windup only offered beer and other soft drinks. Additionally, bar patrons were prohibited from expressing outward signs of affection, such hugs, kisses, or dancing with individuals of the same gender. This bar was a cruising location for homosexual males looking for partners who appeared masculine in appearance and personality; drag queens or other gay men who express effeminate behavior were not permitted in this bar.

The physical appearance of the Windup was concealed and the building was made unobtrusive, as it was impacted by Branson’s desire to ensure a safe, private experience for bar visitors. For that reason, the facade was “very inconspicuous” with painted windows, and a neon sign hung on the door which signals open hours (Branson 24-25). Furthermore, the windows of the Windup were covered with both paint and matchstick bamboo curtains. Forging a family-like atmosphere, the interior of the Windup had a pool table and a number of booths where individuals could freely gather and socialize. Also, the bar stretched across the width of the interior and contained seventeen seats. All of these features highlight Branson’s objective to create camaraderie and companionship.